Author, Aime Marisa, “Documenting the Undocumented: The Struggle for a Legal Identity.”NewNaratif,12 April 2023,https://newnaratif.com/documenting-the-undocumented/ ,Illustrator Alanis Mah

One out of three people in Sabah is struggling for a legal identity, fundamentally affecting their access to various rights and opportunities. This is the personal story of three stateless people and the challenges they face.

Citizenship status is something we often take for granted. Yet, it is so fundamental to our access to the various rights and opportunities that citizenship has been described as“the right to have rights”. Individuals who are deprived of their legal identity are invisible and excluded from society.

In Malaysia, two groups of people are at risk of being deprived of a legal identity: stateless persons and undocumented migrants. Stateless people are those who do not have citizenship of any country, while undocumented migrants lack legal documentation to prove their identity and citizenship. Both groups face significant challenges in accessing basic services, such as education and healthcare, and are at risk of exploitation and abuse.

In Sabah alone, one out of every three people is undocumented. This amounts to about one million individuals with no proper legal identity. Sabah hasthe highest stateless population in Malaysia.

The determination of legal identity is often a complex and bureaucratic process, which can be exacerbated by discriminatory policies and practices. Stateless people often face challenges proving that they belong. In Malaysia, the Home Ministry is responsible for issuing identity documents, and the process can be lengthy and uncertain. Additionally, the children of stateless and undocumented parents are often unable to obtain birth certificates, making it difficult for them to access education and healthcare.

Individuals who are stateless go through innumerable challenges in their everyday lives, living with the uncertainty of their status. To add to these struggles, the mediaoftenportraysthesecommunities in a negative light, invoking fear and xenophobia among the public. They are portrayed as threats to “local” Malaysians, and the issue has come to be seen as a national security issue. Thus, the risk of advocating for this vulnerable population to access proper documentation has been met with visible pushback from politicians and the general public.

This belief stems from ignorance of the complexities of the lived experiences of stateless people in Malaysia. Thus, this article is written to give you a first-hand account of what it’s like to be stateless. Below are the stories of three women who have once lived or are still living without citizenship in Sabah.

Artwork by Alanis Mah.

From Raids to Exile: The Trauma and Resilience of Stateless Families in Sabah

Playing both parental roles is common for mothers who are left in situations where they have to be the sole provider for their family. With a lack of documentation, the challenges are even greater.

Born and raised in Sabah, Bina had to work from an early age to lessen her family’s burden and contribute to the household’s income. As a child, she would help her mother sell vegetables every morning while her father sold water to her community members in the water village where they lived. Bina would fear that no one would buy any vegetables; she faced a lot of pressure from her mother.

Having a lot on her shoulders and very little support, Bina had to stop going to school at thirteen.

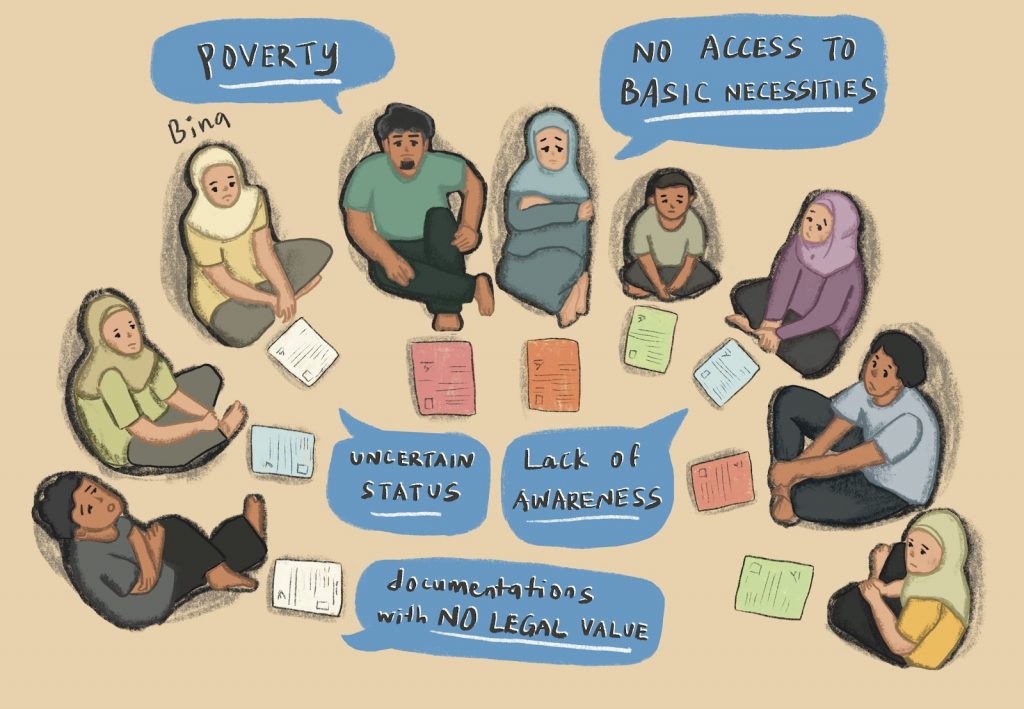

Bina’s father had a Malaysian identity card in the late 80s. Due to a lack of awareness, he did not renew his identity card. By the time he realised, it was too late for him to access a legal identity. On the other hand, Bina’s mother had a document issued by Sabah’s Chief Minister’s office, which at the time was used to register foreigners with no proper documentation status living in Sabah.

Bina is the fifth of seven children. Four of her older siblings did not have proper documentation. Only she and her two younger siblings had their birth registered when they were born. Now, two of her youngest siblings have access to citizenship, but the rest of them still have an uncertain status. Due to Sabah’s unique history of issuingvarious forms of documentation such as the Immigration Pass (IMM13), Special Task Force census certificate, and the Kad Burung Burung (issued in the 1980s by the state government), Bina and her older siblings are left with various papers that hold no legal value in terms of accessing basic rights such as healthcare, education, or getting legally married.

However, these challenges did not prevent Bina from falling in love and starting a family. Her first marriage was a traditional wedding ceremony held in her village, with customs and practices specific to her and her then-husband’s Bajau and Suluk cultures respectively. She had four children with her then-husband, the eldest currently being 17 and the youngest ten years old.

Her first relationship, however, quickly deteriorated. Life with her ex-husband was no walk in the park. She was constantly bullied by her in-laws because of her documentation issue. After a while, it was too much to bear for Bina and she left her now ex-husband. Afterward, Bina is left to support herself and her children.

But among all the struggles Bina and her family have had to endure, one incident has changed her life forever—an incident that inflicted mental trauma on Bina and her children.

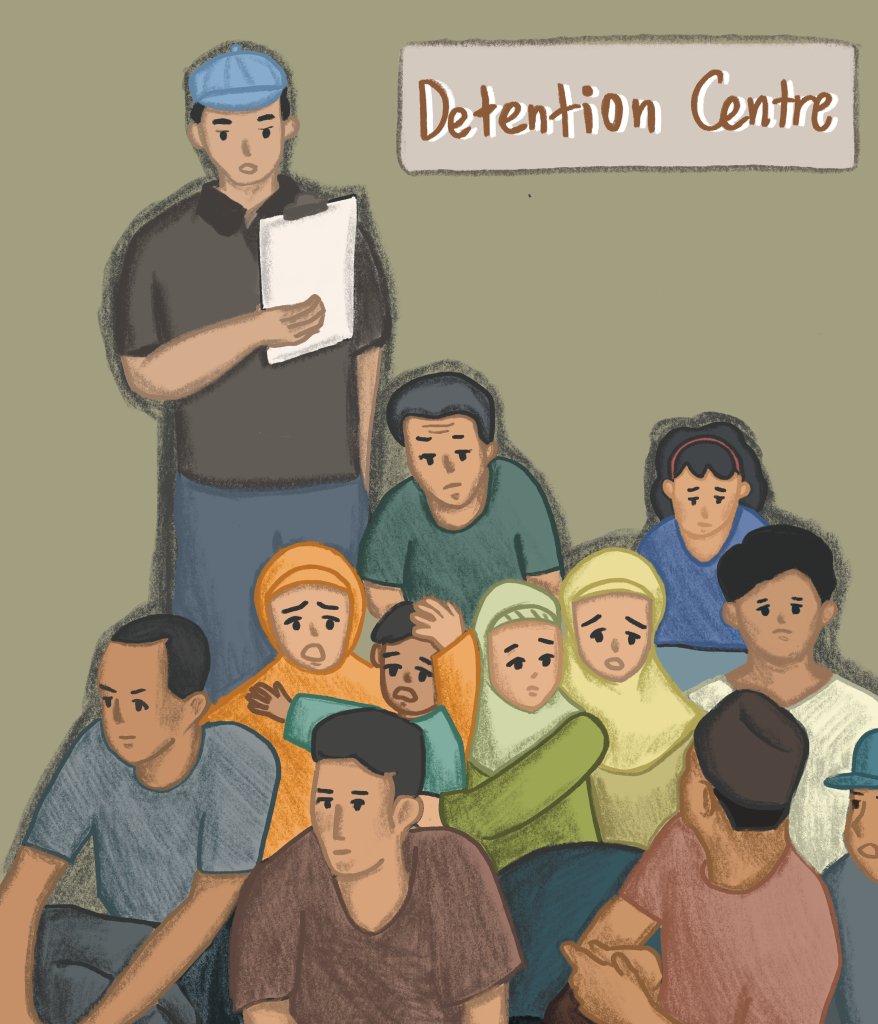

One night after work, the place where Bina was staying was raided by the authorities. That night, the authorities forcefully took Bina and her children and brought them to the Detention Centre, where she would spend the next three months.

There was not enough food at the Centre. While being detained, Bina still had to work to earn money to feed her four children. The overall psychological damage that this has had on her and her children cannot be overstated. Even years later, it is difficult for Bina to talk about what really happened in the detention centre without breaking down.

Artwork by Alanis Mah.

After three months, Bina and her children were sent to the Philippines, where she would stay for the next three years. They were provided with a place to stay, and all her children had access to education.

Still, it was not her home. It was a temporary placement while the government tried to find proof of any family relations she may have in the country. After confirming with the authorities that she was in fact not a citizen of the Philippines and could not access their citizenship there, the five of them were sent back to Malaysia.

The Philippine Embassy had sent Bina and her children back with an official letter, as well as compensation money, to start her life in Sabah. However, when she showed the letters and official documents to the Malaysian authorities on her way back to Sabah, they confiscated all of her children’s birth certificates and all the money she had.

Sadly, Bina’s story is not an uncommon one in Sabah. Yet even with the struggles she went through, Bina is still grateful that she made it home safely with her children, because after all, it is Malaysia that the family regards as their true and only home.

Currently, her three youngest children are able to access education at a local alternative learning center. (Her eldest daughter did not continue her tertiary education, choosing instead to work to support her family and herself.)

Bina’s children only hold their immunisation documents as proof of their birth in Sabah. Aside from the children’s birth certificates being confiscated, her marriage to her then-husband was never legally recognised, thus making him unable to confer his citizenship. At the same time, with Bina being stateless, she has no citizenship to confer.

The procedure to access further papers for the family is difficult, as there are no clear policies on how to process her current document.

She has tried to enquire about how she can at least secure her children’s documentation, but it has thus far been an unsuccessful attempt.

This cycle of generational statelessness is unfortunately a common pattern in Sabah. With no proper access to information and resources, families are left with no legal identity—lives lived under the radar not by choice but due to xenophobia, lack of action, and government inattentiveness. Sabah’s ever-shifting policies do not make it easy for these communities to access a legal identity.

This is clearly not a case of a lack of effort either, as Bina and so many others have tried so hard across various government agencies but are still left with no proper and transparent solution.

Government agencies are not putting in enough effort to develop pathways to access legal documents for stateless people, hence the issue of generational statelessness spans up to three generations in Sabah.

Talks about issuing documents to these communities frequentlystir up the political scene. They perpetuate the negative stigma and lack of political will to really find a solution.

Young as they are, Bina’s children realise the harsh reality of their lives. They wish for a birth certificate or any kind of recognised paperwork, so that at least they won’t feel scared and fearful when they are outside. Regardless, they are still hopeful and are patiently waiting for the day they get to hold their birth certificates once again.

Artwork by Alanis Mah.

Fortunately, Bina now has a good support system around her. Her current partner is considerate of her situation and loves her children as his own. Moving forward, Bina plans to continue to try and find ways to apply for her family’s legal identity. It won’t be an easy path, but for people like her and her children, it’s the only way to access various opportunities and live without fear.

Out of Wedlock, Out of Rights: One Student’s Story

“Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

John F. Kennedy

Kyna was 16, so young and naive when she uttered that phrase in her debate team’s closing speech. She clearly remembers how motivated and inspired she was as she led them to their first victory in the competition. The world, she thought, was her oyster.

Artwork by Alanis Mah.

It took her less than two years to realise that it was not. Or, rather, it could not be. While she had plenty of potentials, she lacked a crucial piece of documentation: a 12-digit identity card that would validate her existence and presence in society. Without it, she did not have this privilege called nationality. What can one do for one’s country when, legally, one does not even have a country?

Growing up, Kyna was sheltered from the truth of her reality. Her two younger siblings also shared the same fate. Her parents were separated when she was just a teenager, so Kyna and her siblings stayed with her Malaysian father.

Kyna and her siblings were unable to receive their Malaysian citizenship because—as was the case with Bina—her parents were never legally married. Like her siblings, Kyna only possesses a birth certificate that states she is a non-citizen.

In 2019, the Ministry of Education introduced the Zero Reject policy that allows stateless children with a Malaysian parent to register their children for public schools. Despite the policy currently not being properly enforced nationwide due to political changes, it has enabled Kyna and her siblings to continue their education.

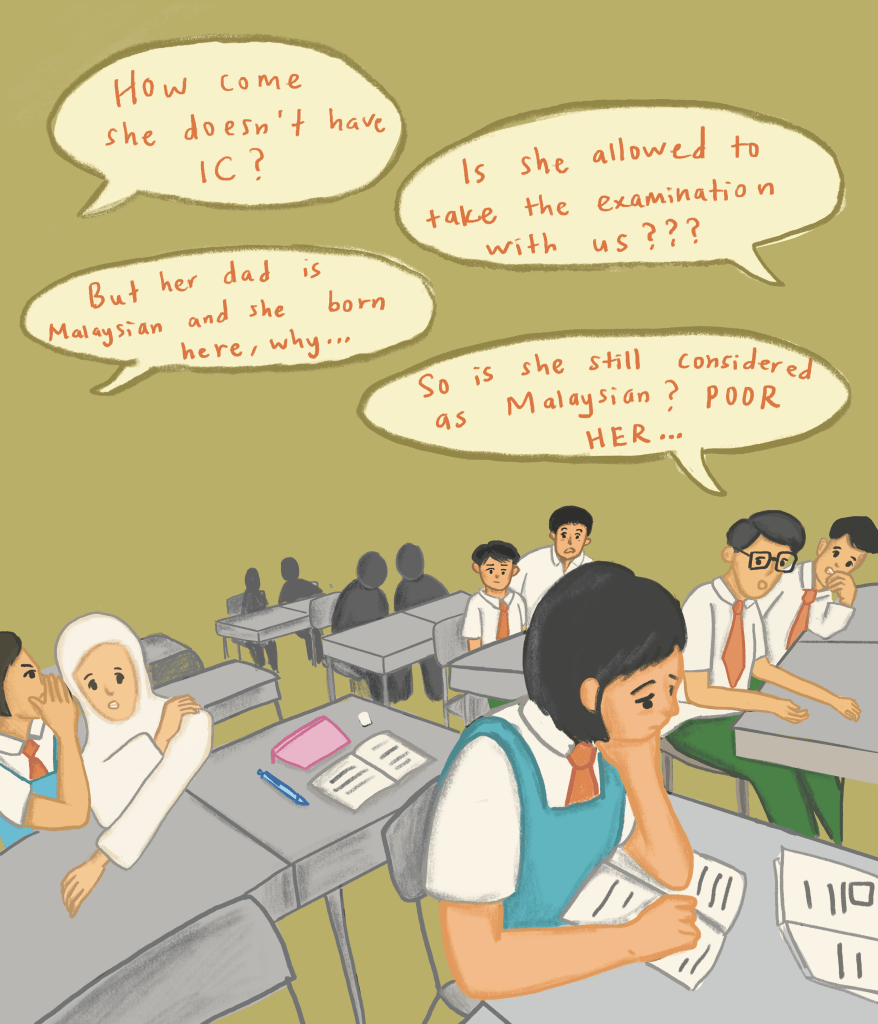

In school, Kyna was a bright student who did well academically and in her co-curricular achievements. However, her lack of documentation prevented her from joining national programmes which required an identity card. Feeling left out and insecure about her situation. Kyna tried to mask it all up and carry on as if she was a normal student. That way, at least she would not be discriminated against amongst her peers.

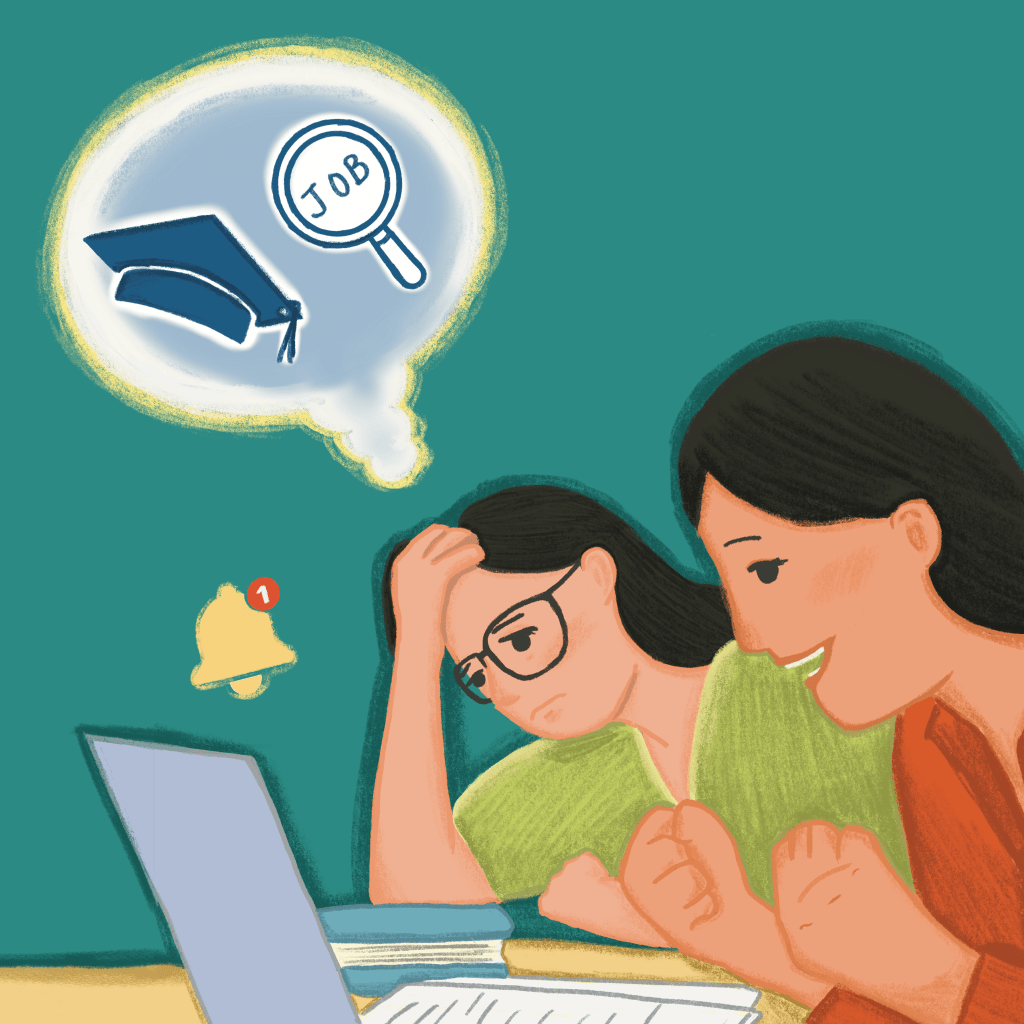

Despite all of this taking a mental toll on her, she still managed to excel in her final examination. She was one of the highest-achieving students in her school. Her success was celebrated. But what’s next for Kyna?

Artwork by Alanis Mah.

High achieving stateless students in Malaysia arenot uncommon. Even with laws and policies that discriminate against them in a system that has failed them, their potential finds ways to shine. Most stateless children only want to be a valuable citizen of their nation and for their life.

Kyna struggled to remain optimistic about her future while, she thought, everyone around her was so lucky and fortunate that they could do almost anything and everything they wanted. Then there was Kyna, who couldn’t even open a bank account or apply to colleges.

She had no choice but to put her education on hold. She tried to find solutions for her future and to further understand her current situation. She tried to learn what it was like for other people, what other methods they followed, and how similar or different her situation was. Only then Kyna learned that she and her siblings are not alone on this journey to fight for their rights and nationality.

The issue of statelessness and nationality ismuch more complex than she thought, especially in Sabah’s context. This is due to Sabah’s strategic geographical location between Indonesia and the Philippines. As a consequence of Sabah’s migration history, mixed marriages between locals and foreigners are common—just like Kyna’s own situation with her Filipino mother.

Understanding the reality of her situation and that thousands of others like her, Kyna was empowered to be an advocate for the issue. She is now part of several organisations that fight for the rights of marginalised communities.

Being exposed to the inequalities in the laws and policies and the exploitation that occurs in vulnerable communities has sparked her interest to pursue an education in law. Her search to further her studies resulted in her finding an educational institution that allowed stateless children to further their higher education. Today, she is a proud university student despite her documentation status.

Artwork by Alanis Mah.

Currently, Kyna and her siblings are still waiting for their second citizenship application results. Her first application was rejected by the government with no justification after waiting for four years. Unfortunately, this is a common scenario for stateless children who are applying for citizenship in Malaysia.

Based on statistics from 2013 to 21 February 2023according to the Home Minister, there are currently 132,272 applications nationwide to become Malaysian citizens. Meanwhile, the stateless population in Sabah alone numbers close to one million.

This difference shows there are still thousands that are still left out. Stateless communities are often unable to even apply because of the lack of documents. The application process is neither straightforward nor transparent.

All of these uncertainties impact what kind of future the applicants could hope to have. Once a rejection is given, and when there are no other options, what else can the applicants do?

Against all Odds: From Red to Green

At the age of twelve, Isabel went through the process every kid in Malaysia would undergo: apply for their identity card (IC). Except that, unlike most other kids in Malaysia, she was deemed ineligible to receive one. On that day, instead of receiving her IC, she was issued a red birth certificate stating that she was not a citizen.

This came as quite a shock. It turned out that this was because her parents’ marriage was registered only after her birth. Thus, by the policy of the ministry, the state regards Isabel as an out-of-wedlock child, meaning her father is unable to confer citizenship to his children.

Her younger siblings, meanwhile, had no problem getting their IC. On the other hand, under Article 15A in the Federal Constitution, Isabel had to go through the gruelling process of citizenship application.

Artwork by Alanis Mah.

The first rejection letter for her citizenship application came in when she was in high school. Still, after that, she pursued another application. The waiting process continued.

This was, of course, very unfair. Her lack of citizenship was not the only problem caused by her parent’s lack of responsibility. Ever since she was a child, she had had to deal with intense fights and hurtful words from her parents. Eventually, they separated when she was nine.

Afterward, the responsibility fell onto Isabel to raise her siblings. She had to make sure they were well-behaved while they were staying at their paternal grandmother’s house after the divorce. She also had to make sure they performed decently at school.

And yet, Isabel’s own school life was falling apart.

Being different comes at a cost, and Isabel went through more than a few emotionally torturous situations in high school. One time, she was called out in front of the classroom by her teachers for her lack of proper documentation.

Being humiliated in front of her peers was especially demeaning. But at the time, all she could do was laugh and pretend it didn’t hurt her deeply.

Isabel remembered her friends staring at her. They did not know this about her. Isabel had deliberately hidden this for fear of having to share a very personal struggle she was going through.

Artwork by Alanis Mah.

As a result of that incident, she completely lost the motivation to study for her exams. What was the point? Without being recognised as a proper citizen, her opportunities were severely limited, anyway.

At school, Isabel tried to distance herself from her friends. Fortunately, she had good supporting friends who noticed this and did their best to cheer her up. They told her she could be the best student if she worked as hard as she did before. But by that time, her spark had dimmed.

Her feelings were exacerbated by the various ongoing processes for citizenship application she was going through. They were ambiguous at best, dehumanising at worst. They made Isabel question her existence in this world.

Having no identity, no access to any basic necessities, and no rights as a human being, Isabel was a ghost in a place she called home. Was she a mistake?

One thing that assured her that, no, she was not, was her newfound faith at the time. She found comfort in her faith. She learned to believe that her worth was not defined by her documentation status, or any other external factor. It was something that brought her peace of mind and self-love.

It was also during this time that she discovered a new procedure to apply for Malaysian citizenship. It started out as a regular check-in at the National Registration Office, where she went to get updates about her citizenship application. The officer at the time told her about an alternative pathway that was available for her situation to speed up her citizenship application. This was because Isabel had a Malaysian parent. That was all she was told of.

After finding out, she submitted another application and underwent an interview with her siblings and father. To her pleasant surprise, she received a new birth certificate that very same day. Her new certificate was printed in green and stated “warganegara”. She was a citizen at last.

As great as this was, the process wasn’t over yet. As the officer told her, “Getting this green birth certificate does not mean you will get your Malaysian identity card, so do not get your hopes up!”

Isabel still had to apply for her identity card, which would take months and was not guaranteed. The waiting game continued as she regularly checked in with the department, hoping for any updates or progress.

Consequently, it was her faith that gave her the strength to persevere. Despite the challenges posed by the pandemic, Isabel’s determination to obtain her IC never faltered. She remained resolute and continued to follow up on her application, even when it seemed like the process would take forever.

After more than a year of waiting, she finally received the news she had been longing for. It was a momentous occasion when she finally went to collect her IC at the age of 23. After more than two decades of being stateless—and being the only one in her family with such a status—lsabel finally had her rights as a citizen.

She could finally live her life without the constant fear of being threatened by authorities, a trauma that had stayed with her for years. With her IC, she now had a sense of legal security that would allow her to live her life fearlessly and pursue her dreams with newfound confidence.

Isabel is currently pursuing her studies in design. Her proudest moment was when she created illustrations for a local news media. She enjoyed the process and the significance it brings. The tables have turned for her, as she now gets to help others.

Artwork by Alanis Mah.

She feels grateful and relieved, but also couldn’t help but feel a sense of unfairness in the process. She knew that there were countless other stateless individuals who deserved their identity just as much as she did, yet had not been as fortunate in the system.

The process that Isabel went through highlights the inconsistency in government policies when it comes to applying for citizenship. After all, according to Isabel, it remains unclear whether her successful application was a new policy implemented across the registration department or simply a channel that was available through sheer luck since other stateless applicants have not heard of such processes before, even when they are in a similar situation. Isabel felt it was the latter.

“Luck” could also be attributed to the personal biases of government officials. There are common stories of applicants being denied access to services in the National Registration Department because of discrimination and the officers’ own sense of entitlement.

Additionally, it also shows how the various laws and policies contradict one another. How is it possible that you are able to obtain a birth certificate that states that you are a citizen of that country but have your citizenship status be in limbo, being unable to receive your identity card?

The risk of Isabel being stateless is still there despite her efforts to prove her case. And we need to remember that this not only affects Isabel. There are many other children who carry a Malaysian national birth certificate until the age of twelve, only to receive news that they are not citizens and be issued a non-citizen birth certificate which leaves them at the risk of being stateless.

Citizenship Should be a Right, not a Privilege: Direct Ways Readers can Help

Bina, Kyna, and Isabel’s stories offer a nuanced perspective on the challenges and struggles faced by stateless individuals in Sabah, Malaysia. As a stateless mother, stateless student, and formerly stateless person, each of them has encountered their own set of difficulties based on their circumstances. These hardships are shared by thousands of stateless people in Sabah every day as the government continues to make policies that are exclusionary, discriminatory, and inhumane.

Currently, there are several civil society organisations that are advocating for the right to citizenship in Malaysia such asDHHRA,Family Frontiers, andANAK Sabah, to name a few. Reforms for equal citizenship rights are at an all-time high in Malaysia, where Family Frontiers have been doing significant work fighting for Malaysian mothers with foreign spouses to confer their Malaysian citizenship to their children abroad. Malaysia is also set to be the host of theWorld Conference on Statelessness organised by the Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion (ISI), Nationality for All (NFA), and Development of Human Resources for Rural Areas (DHRRA).

A few members of parliament have also shown their support for this reform. However, in Sabah, the situation remains complicated and the stateless population is only increasing with no concrete solution in sight.

The government has suggested issuingForeigner Identity Cards to standardise the various identity documents and legalise migrants who have overstayed in Sabah. These communities will thus technically be documented, in the sense that they have some sort of document that holds vague legal powers. However, it is not explicitly stated what legal value this documentation will hold. It remains unclear whether individuals would be able to access healthcare, employment, and education after this process.

On an international level, Malaysia is not a signatory member of any of the important Stateless Conventions such as the Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons 1954 and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. In Southeast Asia, the Philippines is the first and only country to be a signatory member of both conventions.

However, Malaysia has ratified the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Both of these conventions oppose the deprivation of nationality of a child and discrimination in the right to confer nationality for women.

In reality, however, the rights under the conventions are still weakly enforced in practice as they are not incorporated into domestic laws and policies.

Global campaigns for the right to nationality also exist such as the#IBelong campaign by The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) andThe Global Campaign for Equal Nationality Rights. There are numerous ways of getting involved in these initiatives such as learning about the issue and sharing the knowledge with friends and family, these organisations provide easy to understand materials for readers. UNHCR also provides a platform for the public todonate to the cause.

The UNHCR plays an important role in the issue and has laid out mechanisms to reduce and eliminate statelessness, such as the stateless determination procedure. This procedure was designed to detect stateless individuals within migrant groups, in order to guarantee that they receive their entitled rights until they obtain a nationality.

France was the first to establish such the stateless determination procedure in the 1950s and has been protecting stateless persons ever since. Italy, Hungary, and Spain also developed similar programs later on. The methods used to establish these programmes vary, with some countries creating them through laws or regulations while others don’t have a specific legal framework for the process. Perhaps Malaysia would be able to echo the efforts being done by these countries. In this globalised age, it is unrealistic to expect an individual to continue their life with no legal identity.

In terms of access to education for stateless children in Sabah, there have been significant efforts on the ground by local organisations such asCahaya Society,Borneo Komrad andStairway to Hope. These institutions are providing basic education to children despite their documentation. The impact it brings to the community is significant, as New Naratif has previously covered in our articles regardingrefugee education in Kuala Lumpur andhigher education for refugees in Peninsular Malaysia.

Initiatives like these highlight the importance of education to change the fate of their family. Oftentimes, stateless children only want equal opportunities as their peers to live life as normally as they can without the constant fear of arrest or risk of exploitation.

By sharing Bina, Kyna, and Isabels’ stories, we hope to create greater awareness and understanding of the inequalities faced by the stateless community in Sabah. Stateless people are just like you and me, human beings trying to live their lives, only with an extra set of challenges due to their documentation status.

Artwork by Alanis Mah.

Citizenship should be a right, not a privilege. As laid in The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Article 15: Everyone has the right to a nationality. Subsequently, as stated in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Target 16.9 requires that states should, by 2030, “provide legal identity for all, including birth registration”. Let’s not also forget Malaysia Constitution’s fundamental liberties, Article 8 – Equality.

The fight and search for legal identity will continue on as a critical human rights issue. Despite some progress being made, many stateless individuals still face significant barriers to accessing essential services such as healthcare, education, and employment. Government agencies and civil society organisations can work together towards developing sustainable and effective solutions that address the root causes of statelessness and ensure that every person has access to a legal identity. Only then can a more equitable and just society exist where everyone has the opportunity to thrive and fulfill their potential.